In the regulatory and competition policy realm, maximising economic welfare should be the ultimate policy goal. In a previous post, we explained the basic economic logic behind the concept of “welfare”. We have seen how the social welfare that a sector creates is driven by the use of the product or service, and by the utility that consumers extract from that use. We also explained that prices apportion welfare between consumers and producers, and influence both the level of consumption and the incentives to invest.

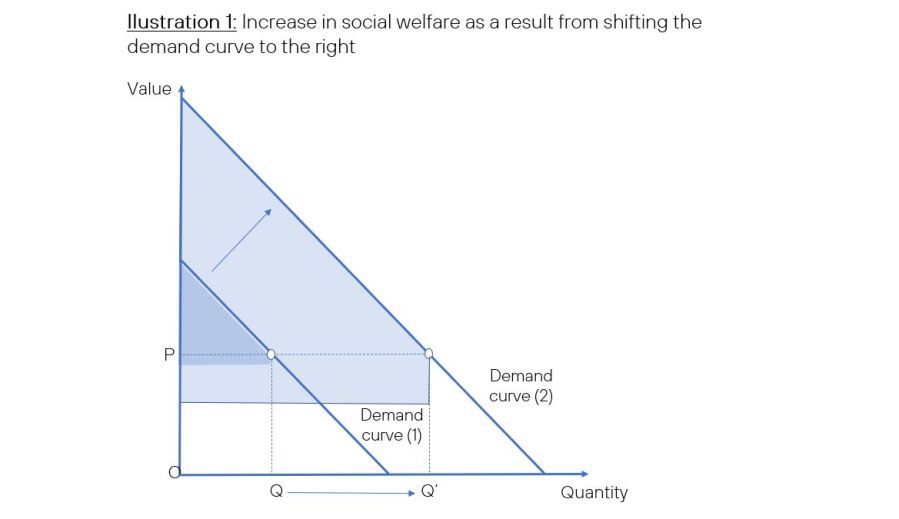

As a result, regulators and politicians use prices to increase social welfare in the short term. However, this puts its future sustainability at risk. Finally, the best way to improve social welfare seemed to be shifting the whole demand curve to the right. In this post, we will explain how this process operates and the role producer surplus has in it.

Utility drives value

You may recall that the foundation for the calculation of welfare is the demand curve. The demand curve represents the value attached by consumers to each unit of product or service consumed measured by their willingness to pay. The graphic below shows that, if the demand curve shifts to the right, the social welfare will increase for the same usage. This is because the consumers extract more utility from each used unit.

Demand shifts may of course be exogenous to the market, without intervention from producers. For example, an unusually hot summer may increase the utility of air conditioning for users. This would shift its demand curve to the right. Far more interesting from a policy perspective, however, are the endogenous changes that producers can induce. They find new uses for their products or, more generally, improve them in some features to better address the preferences of the users.

In order for that to happen, the product has to change, a successful innovation has to occur. How does this process come about?

Competition as a discovery market process

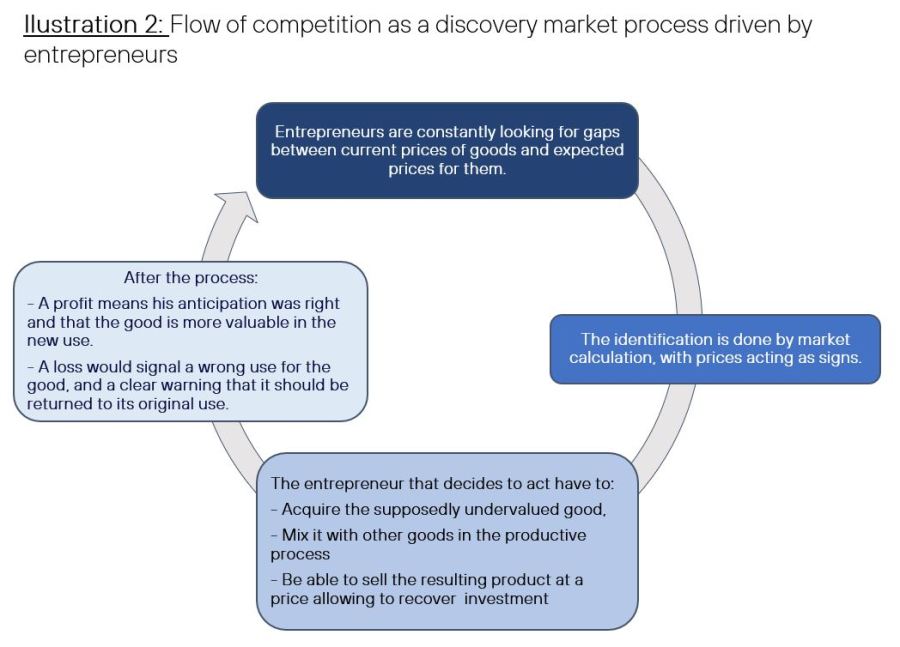

To understand this, it is a good idea to depict the competitive process as a discovery market process [1]. Picture 2 shows this process in graphic form.

The starting point is the fact that information about customer preferences is dispersed among individuals and has to be discovered. Then, the market is a dynamic process of discovery generated by entrepreneurs who are constantly looking for new opportunities for profits. Market calculation is the way to do that, by means of which they make estimates to guide their ex ante decisions. Prices act as signs for entrepreneurial activity in this context.

Detecting a profit opportunity is akin to detecting a more valuable use for a good [2]. The entrepreneur who decides to act has to acquire it, and mix it with other goods in the productive process (always consuming time). Then he needs to sell the resulting product at a price allowing him to recover the whole investment, together with the interest rate for the passing of time (time-preference rate). If, after the whole process, there remains a profit, it means his anticipation was right. Therefore, the good is more valuable in the new use than it was in the alternative one. On the contrary, a loss would signal a wrong use for the good. This would issue a clear warning to return it to its original use.

If there is a profit, more amounts of the good should be directed for the new use. The same successful entrepreneur is in a privileged position to keep profiting from his/her finding, or by other entrepreneurs attracted by profits. The process of imitation goes on up to the moment in which the profit disappears. The reason is an increase in available stock for the resulting product or an increase in the prices of the initially undervalued good. This last increase will in turn act as a signal for profits, unleashing new competitive process in other markets.

The pillars underpining competition

Profit opportunities depend on the gaps between current prices of goods and expected prices for them. Changing in prices may thus prompt profit opportunities. A raise in a price signals an increase in the relative scarcity of the good. This is the result of an increase in its value for individuals (for example, due to a new use), or to a decrease in the available stock. A reduction in a price signals the opposite.

The market is thus best described as a search for increased value in a context of uncertainty, and its operation may be summarized around four key pillars [3]:

1.- Competition. Understood as rivalrous activities of market players in search for new pieces of information. The main goal is to better satisfy customer needs.

2.- Knowledge and discovery. The competitive process does not only mobilize existing knowledge, but also generates awareness of opportunities. However, no one at all knew of its existence.

3.- Profit and incentives. Profits are the mere subtraction of known costs from known revenues, but as the incentives to locate gaps between costs and revenues. In other words, profits are a sign that goods are more valuable in other uses than in the current ones.

4.- Market prices: in each moment, they are the exchange ratios between market participants; they provide information to entrepreneurs on the current valuation of goods, and, thus, on the opportunities of profits.

The role of producer surplus in causing demand shifts

Shifting the demand curve to the right, and the consequent increase in social welfare, is not an easy process. On the contrary, it is a process subject to a high degree of risk and uncertainty [4], because the improved features and characteristics of a product that are valuable to consumers are not known beforehand. Moreover, investment in goods is required before being able to test the entrepreneurial idea. So, entrepreneurs confront a trial and error procedure as the only way to increase the utility for users. Such procedure requires resources but often ends in failure.

Even if there is no guarantee of success, the more trials the entrepreneur is able to carry out, the greater will be the chances of finding a better product. This could shift the demand curve to the right.

How to make a product valuable to consumers is at the core of modern management theories. This idea underlies, for example, the “Lean Start-up” of Eric Ries which explore how to efficiently use a constrained budget for innovation. The discovery process is similar to an airplane lift-off, with two possible outcomes: success or failure.

The runway that a start-up has left, that is, “the amount of time remaining in which a start-up must either achieve lift- or fail” is often measured “by the remaining cash in the bank divided by the monthly burn rate, or net drain on that account balance” [5]. Of course, this does not only apply to start-ups but to any consolidated firm, because of the changing and uncertain nature of consumers’ preferences. In fact, Ries goes on to say that “The true measure of runway is how many pivots a start-up has left”, in view of its available resources.

In financial terms, this means that shifting the curve of demand to the right requires Capital Expenditure (CAPEX). The more CAPEX invested, the more ideas will be subject to the trial and error procedure, and the more possibilities of succeeding in achieving that shift.

Consequently, the CAPEX a firm will be able to commit to the discovery process is directly related to the current producer surplus it is able to keep, as this surplus is immediately available for the acquirement of new goods with which restart the process.

Then, in anycase, increases in social welfare should be seen with a certain delay with respect to the CAPEX invested, and the more CAPEX invested, the larger the increase observed.

In a nutshell

1.- Producers can increase social welfare by inducing shifts in the demand curve to the right. This implies finding new utilities for goods.

2.- The way to achieve this is to understand competition as a discovery market process.

3.- In the discovery market process, entrepreneurs anticipate resources in a trial-and-error process to learn about consumer preferences. Most of the times, their ideas fail, but when they succeed, the demand curve shifts to the right and social welfare increases, often in a spectacular way.

4.- Anticipated resources correspond with the financial concept of CAPEX. The higher the producer surplus, the more CAPEX they will be able to invest. Then, the more chances they will be able to find new valuable uses for their products, thus increasing social welfare.

In the next post of this series on social welfare we will apply the methodology explained in this and the previous article. The aim is to measure the social welfare contributed by the telco market both in the European Union and in the United States, and we will contrast if the relationship just explained between CAPEX and social welfare holds in that case. Interesting? Stay tuned and subscribe to our weekly newsletter for all the latest news.

Footnotes:

[1] See Hayek F.A. (2002). Competition as a discovery procedure. The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, Vol. 5(3), p. 9-23.

[2] In economic theory, there is a distinction between goods of first order (goods ready for consumption) and goods of higher order (factors of production). In general, the activity of the producers consists of mixing factors of production to achieve a product. This product may be or not a good of first order, but the analysis does not change.

[3] Kirzner I.M. (1985). The Perils of Regulation: A Market Process Approach. In R.M. Ebeling (1991): Austrian Economics: A Reader. Hillsdale, MI: Hillsdale College Press. See pp. 629-633.

[4] As may be attested by any statistic on business failures.

[5] See Ries E. (2011). The Lean Startup. Crown Publishing, chapter 8. It is this book that introduces the concept of “Minimum Viable Product” (MVP), so generalized nowadays.