In recent days a debate has arisen about the importance of Corporate Reputation for companies. The father of the controversy is the Schumpeter blog in The Economist magazine, which published an article entitled “What’s in a name? Why companies should worry less about their reputations”. Schumpeter’s main argument is that “the best strategy is to think less about managing your reputation and focus more on providing your customers with the best products and services you can” because “if done right, customers will say great things about your products”. Continuing along these lines, Schumpeter takes a moment to criticise the fact that the reputation-management appears to be split “between communication and public relations specialists (who look for the best spin in their headlines) and managers of corporate social responsibility (who aim to improve the world and also be thanked for it)”.

Read in this way, I agree with Schumpeter. The reputation of a company, like that of a person, is built above all on facts, not just with words. And, generally, what says the most about a company is its range of products and services on offer. This is how the reputation of the big name brands has been built over time: with their range of products and services.

However, I cannot agree with the underlying argument in the article. For Schumpeter, reputation is only built by placing an emphasis on products and services. And while that may be true… it is not the whole truth. Like it or not, companies have to manage their reputation because, simply put, they have to differentiate themselves in the market. They have to get to occupy a space in the minds of consumers which is “original and unique”, and this is even more true in a highly global and interconnected world. They have to find levers that connect with emotions, not only with reasons (how many impulse purchases are made, regardless of the dictates of reason?). They have to earn the trust and admiration of their customers. Simply put, they need to have their own distinct personality in order to exist.

Only placing an emphasis on products and services leads to a serious risk: competing exclusively on price. And we should not forget that in today’s world the West cannot compete on price. The West (the US and Europe) has to compete on added value. And for that it is necessary to know what other levers are perceived by consumers as sources of value.

Therefore, companies have to worry about managing their reputation. This is just in order to survive.

If this is so… Why does this Schumpeter blog make an attack on reputation management by companies? In my opinion, it is because it equates Reputation to “Fancy Marketing”, to Communication and Public Relations. It is not the first or the last time that authors and business managers have considered that “real” business management and management of communications are two parallel worlds. They simply do not realise that the reputation of a company (like that of a person) is the sum of what it does: of its actions (management) and of what it says (communications). They just do not realise that there is no communication policy that can make up for bad management. While, on the contrary, it is difficult to place a value on good management without careful communication. I remember one day, while discussing a sponsorship linked to culture, a senior manager said to me: “That’s fine for reputation, but what really matters is the quality of service”. For this person, as for Schumpeter, reputation and management are two parallel worlds which are not connected.

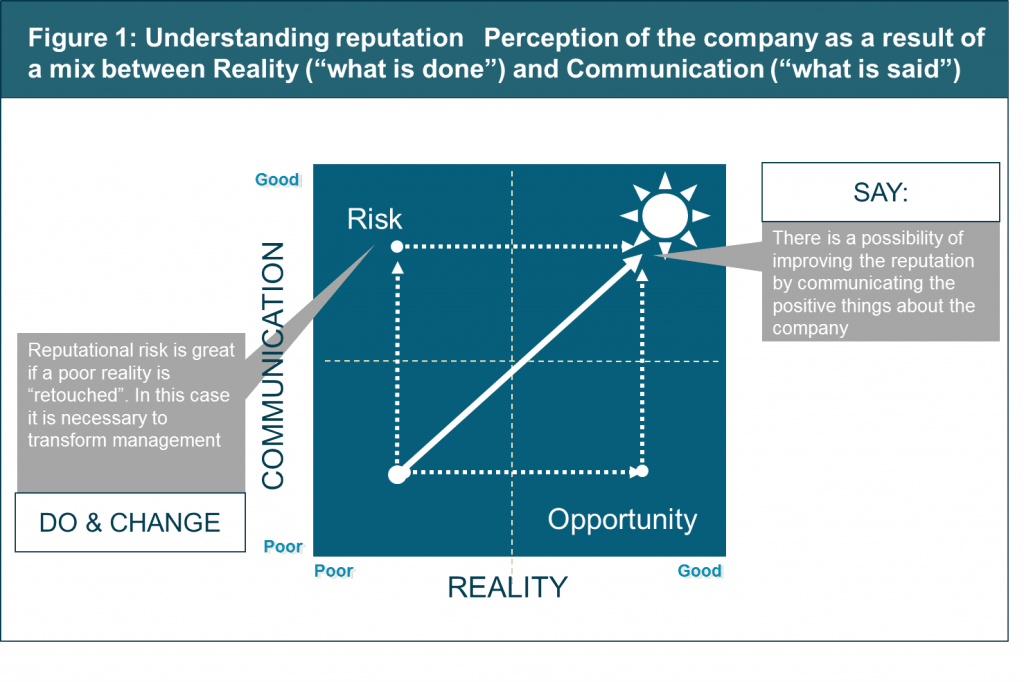

Why does Schumpeter identify communication and reputation with “fancy marketing”? Because, as for so many authors and managers, this minimises the impact of perception. What I mean is that Schumpeter simplifies and fails to understand that we all form an opinion on something or someone based on the sum of two factors: reality (the facts) and perceptions (subjective interpretations of those facts). Therefore, as described in Figure 1, the reputation of a company (like that of a person) is the result of a combination of these two factors: reality and perception. Not merely isolated events (although they have a decisive impact) or perceptions taken separately: all of them together. Furthermore, we enter a danger zone when what is perceived of us is better than what we indicate with our deeds or our data and, on the contrary, we enter a zone of opportunity when what is perceived of us is worse than we really are.

Therefore, to manage the reputation of a company it is necessary to take into account these two variables: the doing (including the improvement of what we do not do well) and the saying (looking for “hidden gems” within the company that we have not yet drawn attention to).

Why do we work like this? Perhaps because human beings are complex and simple at once. Perhaps because, although we do not understand it, it is common, when faced with the same fact, for two people to give it radically different interpretations. Perhaps because the world is not binary (0. 1) and is filled with greys, light colours, dark colours and all the shades in between. Or perhaps… you tell me!

A good explanation for the “confusion” caused by perception can be found in the work of Professors Carl R. Rogers and F.J. Roethlisberger who, in their article “Barriers and Gateways to Communication” (Harvard Business Review, December 1991), claim that assumptions and perceptions are a major barrier to communication (to which we need to add others such as different psychological positions between senders and receivers, defensive communication, the tendency to judge others and personal implications).

For these academics, perception is the mechanism through which people complete incomplete data taken from reality in order to understand and encode the messages they are receiving. In other words, to understand complex messages we people need to rely on the “hard drive” of our brain where we store memories, experiences, data, facts, comments, etc. Only in this way can we decode reality, understand it and make it comprehensible to our own judgement.

Perception, therefore, is a complex mechanism, which is conditioned, inter alia, by the impact of psychological figures which include: stereotypes (“moulds” into which individuals are classified), the expectation effect (the generation of expectations about others), the “projection” effect (attribution of own feelings to others), and, above all, the “halo effect”. This last effect, described by the psychologist Edward Lee Thorndike (1874-1949), refers to the natural tendency that all human beings have to form an opinion about a person (in this case, about a concept) based on a trait of his or her personality that particularly stands out above all the others.

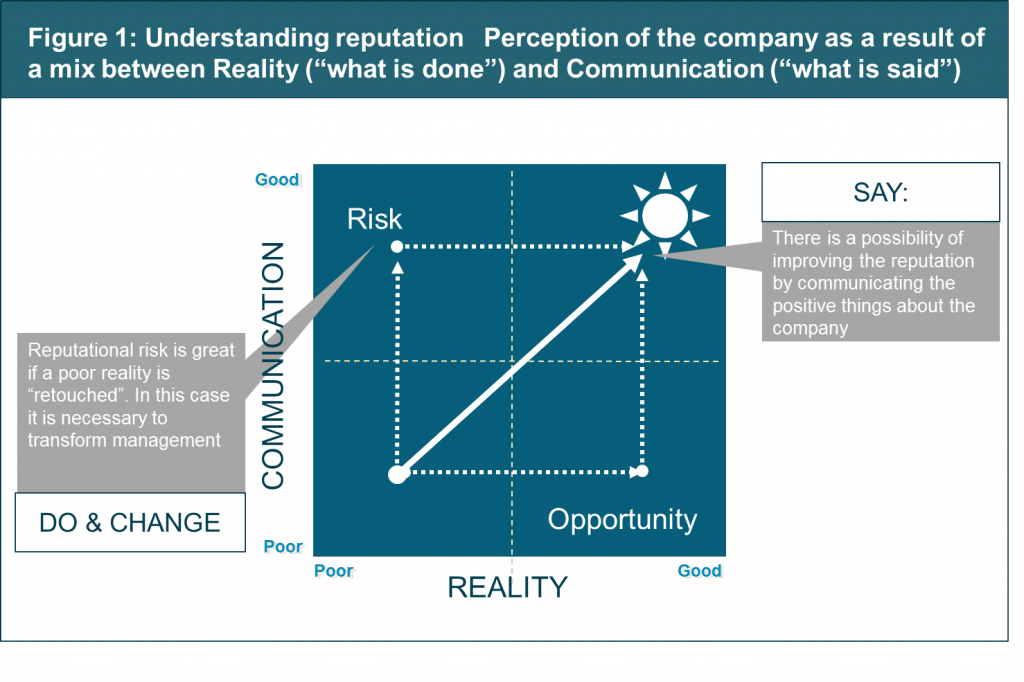

Therefore, to manage reputation, it is necessary to understand that perception is the result of two vectors: the facts (what is done) and communication (what is said). Not just facts, not just perceptions: both things together. In order to manage this mix, Professor Charles Fombrun, Professor Emeritus at NYU Stern and President of the Reputation Institute, in November 1999 created, along with Naomi Gardberg and Joy Sever, the Reputation Quotient tool, the first instrument to measure reputation. In this first tool, Fombrun identified seven levers around which reputation was built (and around which it was necessary to “Do” and “Say”): the goods or services on offer; being a good place to work; the integrity of the company’s behaviour; the quality of its management; its innovative capacity; its positive impact on society, and its financial results.

Years later, in 2005, the companies that were part of the Corporate Reputation Forum (Agbar, BBVA, Repsol, Telefónica, Abertis, ADIF, Ferrovial, Gas Natural, Iberdrola, Metro de Madrid, Renfe and Sol Meliá), together with the Reputation Institute, conducted an adaptation of the Reputation Quotient to try to understand why not all their dimensions had the same importance to consumers. The result of this joint work between the now-defunct FRC and the Reputation Institute Spain, the current RepTrak model includes different weightings by attribute, as shown in figure 2.

Six years later, the model is being used not only by the companies listed above, but also by top multinationals worldwide.

Now, six years later, and with a background of over 3 million direct interviews among the general public in more than eight countries based on a constant questionnaire, we can even fine-tune a few more facts:

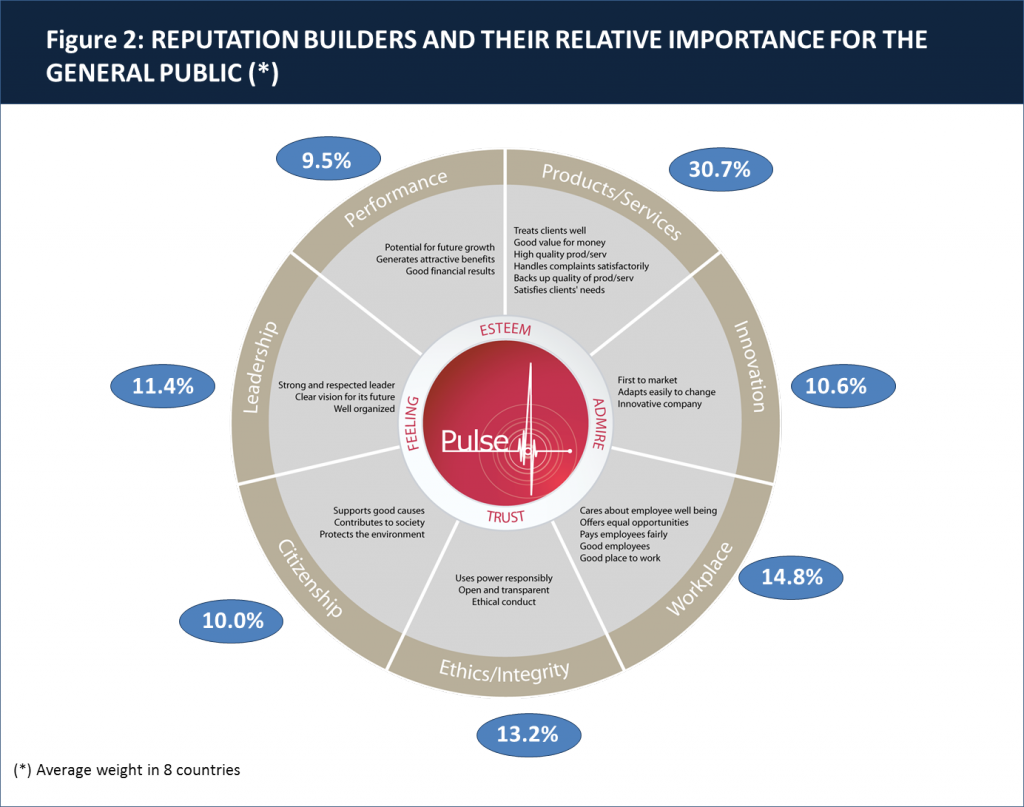

- Firstly, we can state that, in the six countries for which we at Telefónica have comprehensive information, the most important variables remain the services on offer and being a good place to work (in line with the claims made by Schumpeter), although there small variations in the weighting of each variable. Figure 3 shows the weighting distribution by category and country.

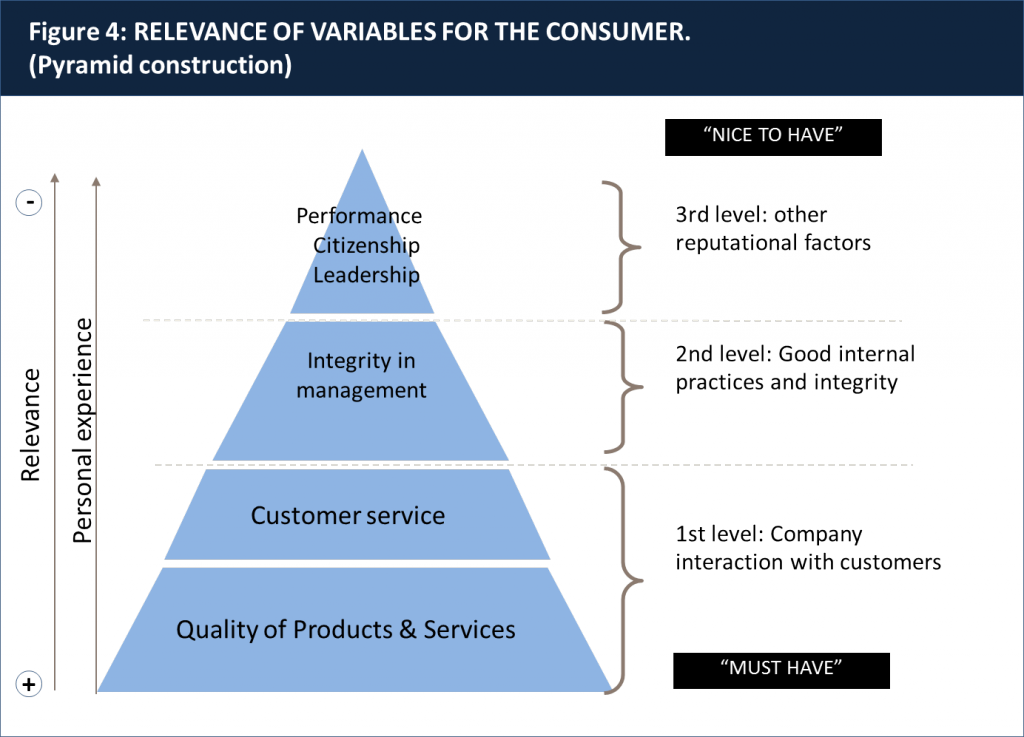

- Secondly, we can also state that these seven factors, in addition to having different weightings, have a pyramid form: the base of everything is the range of goods or services on offer, the second level is the integrity of the company (the fulfilment of its promises and ethical behaviour), and finally, all the other attributes on a third step. In other words, what matters most is the range of products and services on offer… but commercial variables are not sufficient to achieve a good business reputation (about 70% depends on other variables, although they may be subjected and subordinated to the main factor). Figure 4 shows how the reputation variables behave in the mind of the consumer.

Since this is an analysis based on facts and realities (backed by more than 3 million interviews in 8 countries over 6 years), why do we still give a negative connotation to reputation management? Why link it to the manipulation of consumers? Why reduce it to the category of “Fancy Marketing”? I do not understand why there is no problem in saying naturally that this or that person has a good (or bad) reputation, and then to place a negative halo over those companies that want to manage their reputation and accuse them of being “manipulative”.

Well, actually I do understand it. The answer is not unequivocal and it deserves another post. But I would like to propose an idea: “I fear that those responsible for “managing the business” and those who “manage communication/reputation” have usually lived in two parallel worlds. In general, they each speak different languages. On the one hand, members of the first group (focused on the business) live under the pressure of short-term results and their obsession is usually with short-term sales, and they do not consider in their mental equation anything that does not directly impact the bottom line. On the other hand, we in the latter group (who deal with intangibles) usually focus on the medium- or long-term to keep relationship bridges open with the “other” stakeholders, those who are not customers (employees, shareholders, media, civil society, etc.) and around them we build up “the public discourse” of the company that goes beyond its business and financial results.

What is the conclusion? Well, in the end, with the goal of “everyone doing their job”, or “maintaining the status quo”, both parties (management and communicators) are located de facto in parallel worlds which are not connected. The challenge is to overcome this situation, to realise that the consumer has only a single brain and that it only takes on one idea: the company as a whole, not bits of it all working independently. Maybe now it is up to us, the managers, to think of the company as a whole, rather than everyone taking up his/her plot of land. How to do it and overcome it… in an upcoming post.